**This is the 3rd post in a series on our rainwater system. Read Part 1 and Part 2***

Returning to our conversation about rainwater, we know 45,000 gallons of rain runs off our roof during an average rain year, and 55,000 this year. Let’s say our household uses 5,000 gallons per month, the U.S. average for a family of 2. With virtually all of our rain falling from October through April, we’re pretty sure our tanks are constantly full during these months and all that falls from the sky is overflow after household use. 5,000 gallons/month for those 7 months is a total 35,000 gallons of household use and 10,000 gallons of overflow to the storm drain. We just installed our own water meter in the garage, so I won’t have the actual numbers until next August, but it’s safe to estimate that, in this rain year, we had 10-20,000 gallons overflow. With this reality in mind, it was our choice to construct a small wetland to catch as much of that overflow as possible and keep it from going to the street and overburdening the city’s storm drain system.

To give you an idea of how this came to be, look at the pictures above. The first one is our friend, Amy, pulling nails from boards we saved from the old house that stood on this property. Two years later, where she was standing has become the wetland along the sidewalk in front of our house. The next photo shows the new sidewalk in the same spot with an 18-24 inch deep ditch on the house side. We decided to take advantage of the excavated ditch to establish our wetland. We laid a 4-inch perforated PVC pipe the full length of the ditch to distribute the rainwater, then covered it with crushed rock and river rock. From the close-up of the junction, you may be able to get an idea of how we plumbed the overflow line so that rainwater fills the wetland first. So our overflow lines carry excess water under our backyard garden directly west toward the street from our 3 storage tanks. It flows into the wetland first. When the wetland is full, the water flows on and exits to the street through a bubbler and flows to the storm drain. It wasn’t until March when we first saw a small amount of water overflowing out the bubbler to the street. The vast majority of the 10-20,000 gallons flowed into the wetland.

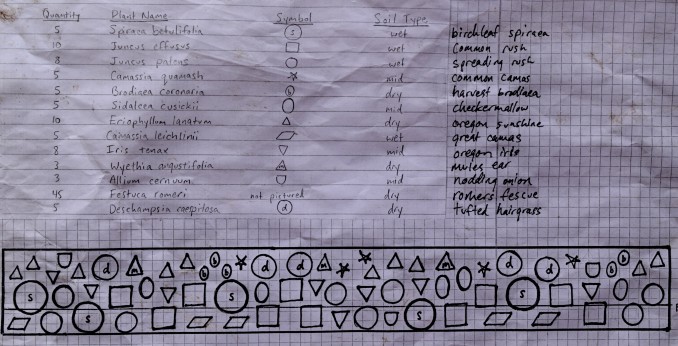

We met landscape designer Adam Kotaich (541-999-2419) at our local native plant sale and paid him to work with us on the wetland design and help us find the prairie natives we wanted to use. He did an amazing job for us.

We covered the slope above the ditch (a potential weed bank) with several layers of cardboard and wood chips. We planted higher plants through the cardboard. Lower-lying plants we placed among the river rock by putting small amounts of soil beneath each plant.

In our little wetland prairie along the sidewalk in front of our Net Zero home, we have planted these 14 native prairie species:

- Birchleaf Spiraea (spiraea betulifolia)

- Checkermallow (sidalcea cusickii)

- Common Camas (camassia quamash)

- Great Camas (camassia leichlinii)

- Common Rush (juncus effusus)

- Spreading Rush (juncus patens)

- Field Cluster Lily (dichelostemma congestum)

- Harvest Brodiaea (brodiaea coronaria)

- Mules Ear (wyethia angustifolia)

- Nodding Onion (allium cernuum)

- Oregon Iris (iris tenax)

- Oregon Sunshine (eriophyllum lanatum)

- Roemer’s Fescue (festuca romeri)

- Tufted Hairgrass (deschampsia caespitosa)

Birchleaf Spiraea:

Checkermallow:

Common Camas:

Common Rush and Spreading Rush:

Field Cluster Lily:

Harvest Brodiaea:

Nodding Onion:

Oregon Sunshine:

Roemer’s Fescue:

Tufted Hairgrass:

In early Spring, our tiny slice of native wetland prairie came to life in our front yard in the City of McMinnville. We’d been waiting all Winter. The audacious colors of it would’ve been enough, but there’s an added joy to the bloom.

You see, our overflow garden is a minuscule remnant of the world that once was in the Valley of the Willamette. It is for us a fragile memory of the culture that resided here long before my latecomer ancestors traveled the Oregon Trail, bringing a culture that obliterated native habitats and peoples. Less than 1% remains of the wetland prairie and oak savannah that dominated the landscape until the late 19th century. Of course, the Kalapuyans and their ancestors are also mostly gone, herded to places like Grande Ronde here in Yamhill County on too many Trails of Tears, trod with genocide and disease, broken treaties and predatory religion.

My Uncle Elvan witnessing recently, at the Pitney Family Reunion, said he’d seen this original ecosystem on our farm West of Junction City as a boy. Our father (his older brother) remembered watching men on horseback, herding cattle and sheep on that prairie. All he could see above the native Tufted Hairgrass was heads and hats. When he was 14, Dad watched as the last uncultivated piece was plowed for the first time. That was 1934.

I’m sure Dad and his brother were aware of at least a few of the hundreds of native plants on the original prairie. These and their neighbor plant and animal species sustained human cultures for thousands of years. Tribal women dug Camas with forked sticks and elk antlers, roasting and drying the roots in pit-ovens. They were ground, pressed into cakes and stored for food and trade. They found the Nodding Onion perfect for flavoring wild fish and game. The corms of Brodiaea and bulbs of the Cluster Lily were dug in early May and boiled or cooked in earth ovens. They were called Kalapuyans, literally People of the Long Grass, because their word for the long grasses was kalapuya. They ignited fires in late spring and fall to create lush meadows of the long grasses like Roemer’s Fescue and the Tufted Hairgrass to entice elk and deer down from the foothills.

This ecosystem and the human and animal communities that stewarded it was an elegant hydrology. What our native prairies functioned to do for eons was manage storm water. Much of the land occupied by these species was under 1-3 feet of water November to March. The prairie plants, reptiles and rodents filtered and refreshed the waters as they slowly seeped from the lowlands back into the rich estuaries of marshes, streams and rivers bringing life-giving nutrients to the land and water, protecting ancient spawning beds from being smothered in toxins and silt.

Our rainwater system at 928 NW Cedar was conceived within a broader world-wide conversation about the scarcity and pollution of both water and human community. Our rain contractor, Michael Martins visited the other day to change our filters for the first time (www.OregonRainHarvesting.com, 503-680-3460). He told us he’s been asked to meet with the mayor, city council and city managers of a city nearby, to talk about rainwater harvesting as one solution for what is becoming the catastrophic challenge of stewarding storm water and run-off. We now know global heating is leading to more intense weather events. As we witness storms dropping more rain than we’ve ever seen in shorter periods of time, our conventional stormwater systems are unable to handle the load. Larger volumes of run-off means more erosion, silting and pollution. So their City is going to try some residential pilot projects in some of its neighborhoods to see if they can make an impact in reduction of stormwater volume with rain catchment and municipal bioswales. We are beginning to see these water works of the future all around the world now, seeking to keep rainwater longer on the land where it falls with strategies such as ours and the creation of bioswales, rain gardens and wetlands in public and private spaces. It is becoming abundantly clear that our survival on this Planet has much to do with the rise and fall of water. It is a call to gather our best selves around this new hydrological moment and summon the ancient wisdom of the long grass prairie.

In early Spring, the first flower to bud in our street-side swale was the Oregon Iris. In full bloom it awakened a beauty we didn’t remembered we’d lost. Our tiny prairie ditch has saved a few droplets from the drain, it’s true. Not such a big deal when we consider all water-dom. Our little slice of prairie won’t bring back the song of the meadowlark or the host of forgotten butterfly species whose existence depends on the Tufted Grass. No grasses will be set afire in this place. No elk will come. But maybe it’s a start. We hope so.

It’s September now and our mini-marsh bed has dried into the smells of the dog days. This morning, at dawn, I looked out there from the front window. In my imagination I saw an old Kalapuyan woman stooped to replant a camas bulb she’d dug with an elk horn last Spring. She paused from her work for a moment, stood and turned to me. The expression on her brown weathered face said, “Together, my Anglo friend, let us see what wisdom comes with the fall rain.”

You can read the final installment in my Rainwater Catchment Series here (it’s a song!).

Recent Comments