There’s an extremely important election on Tuesday, November 3, 2020. Will you please join me in casting a ballot? “I’m not asking you to vote for particular candidates, only to be a voter, so our elected representatives are accountable to all of us. Vote Forward (votefwd.org)

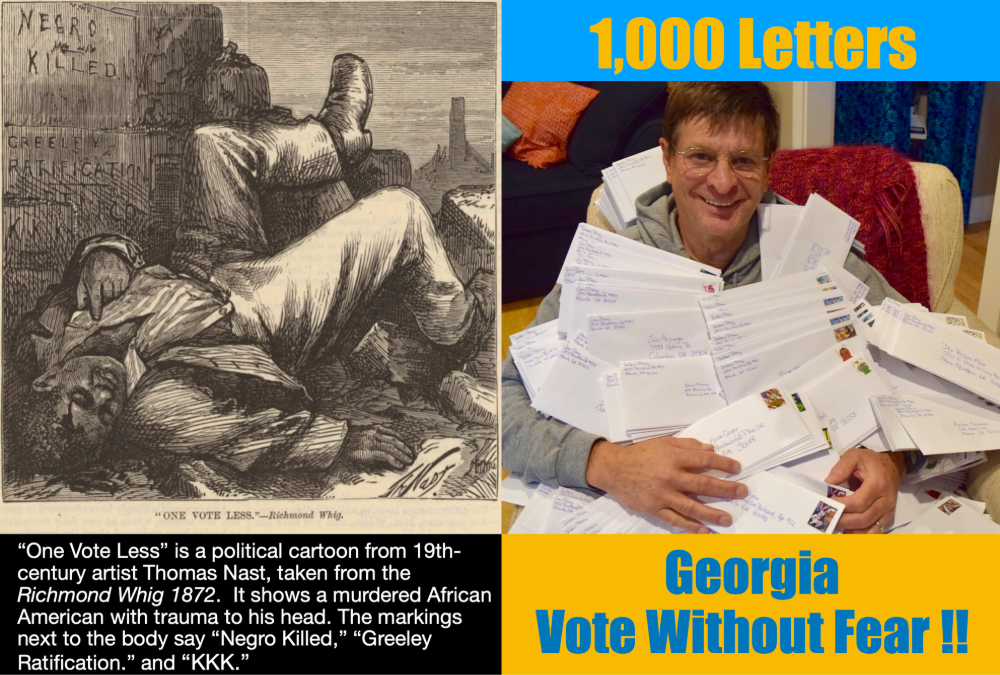

Today is the day. It’s a big one. And way bigger than I, as a white man could ever comprehend. Debbie and I decided our main contribution to democracy in Election 2020, beside voting ourselves, was encouraging others to vote. We joined project “Vote Forward,” to send letters to those in swing states least likely to vote. They were formatted for us with the words quoted above, simply encouraging folks to be voters, no matter their allegiance. Each letter held a space for us to hand-write 3 or 4 sentences of why voting is important to us. October 17, we put 1,000 letters in the mail. We’ve no idea what our work will mean in the November 3 outcome, but we thought this was our best shot.

We had a choice of where to send our letters. Most of them went to voters in Georgia. It takes a long time to hand-address, hand-write, stuff and stamp that many. We had a lot of time to think about what we were doing. As I wrote each name, I imagined the life of each of the citizens who’d read my letter and what their lives might be, who their families are. I wish I knew what realities either expand or limit their ability to become who they were born to be as children of God in the United States of America. Looking at the stats, I knew almost 50% would be people of color. At least a third of them African Americans.

I don’t know Georgia. But part of my reason for choosing to mail letters there was the reality of voter suppression. In truth, as a privileged white male from far west Oregon, I’ve known very little about the historic, carefully systematized, well-funded and often violent strategies to deny, especially African Americans, the right to vote. Committed as I am to helping other privileged white people get a clue, I decided to do some poking around in history while I was writing. At first I was really curious about the names of Georgia towns and cities. They’re different than Oregon. I was addressing to Athens, Macon, Marietta, Valdosta, Decatur, Lithonia, Alpharetta, Moultrie, Douglasville and Millen; Sharpsburg, Dunwoody, Savannah, Hephzibah, LaGrange, Fairburn and Atlanta and many more.

A recurring name was Brunswick. The more I wrote that place, the more Brunswick, Georgia seemed like a place I should know. Of course I’d heard it on the news. Ahmaud Arbery used to be alive in Brunswick. His mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones had “the talk” with her son when he was learning to drive. You know, the conversation I’ve never even thought of having with my white kids, where Black parents warn their children how to stay safe when encountering law enforcement. She said “I didn’t think him out jogging would put him in danger.” But her 25-year-old son was shot to death February 23 in Brunswick, Georgia. As I pursued the story I learned it wasn’t until May when Travis McMichael, his father, Gregory and William Bryan Jr. were charged with his murder. And now I have learned that Arbery’s death has been labeled a lynching, which is defined as a killing by three or more people claiming extrajudicial reasons to kill. (1)

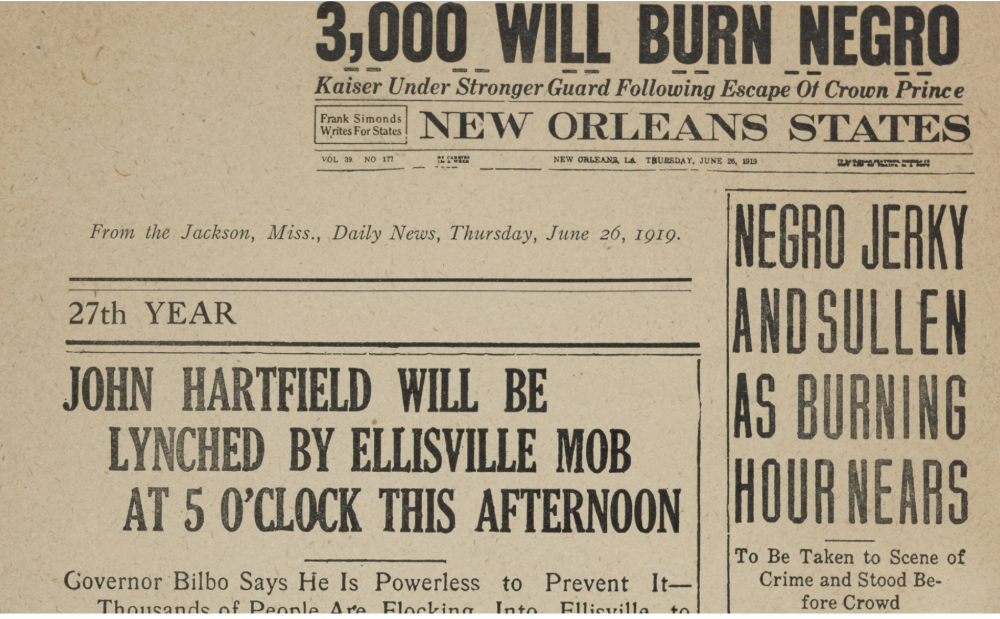

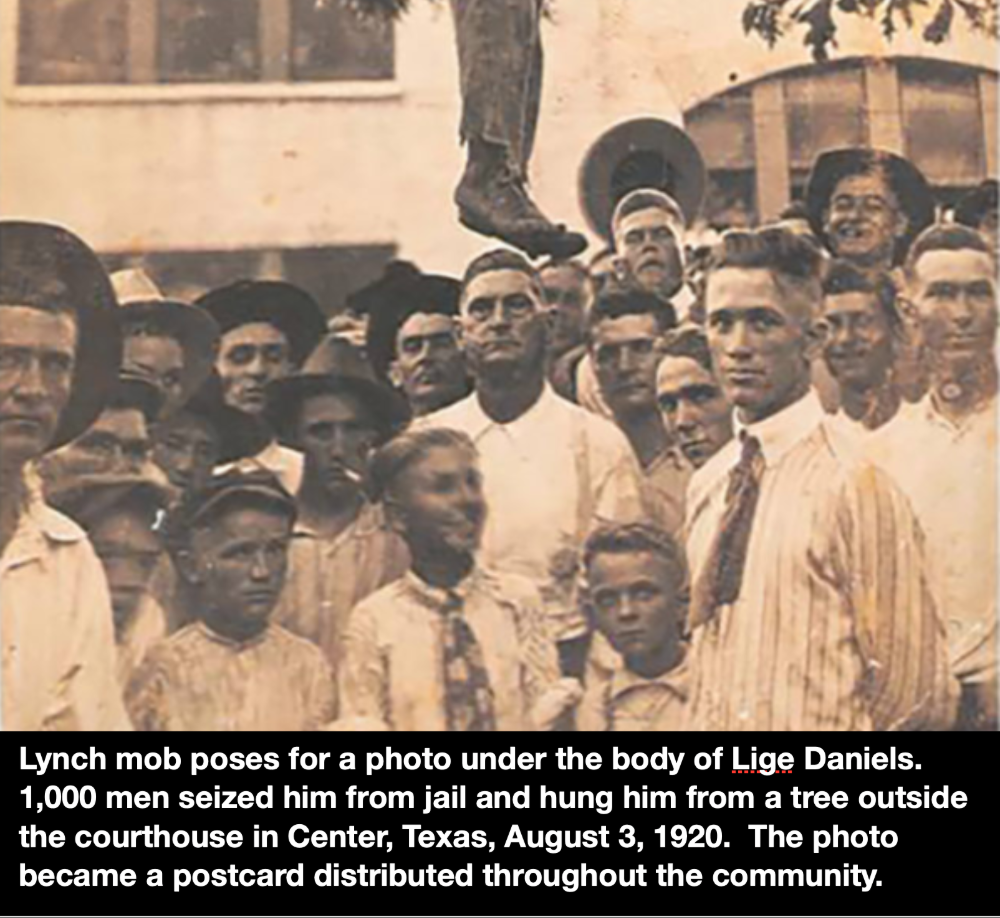

Lynching? What do I know of lynching? As I studied the Ahmaud Arbery tragedy on line, I couldn’t avoid the historical reality of lynching in Georgia. The Equal Justice Initiative (eji.org) has identified a total of 4,084 “terror lynchings” during the period from the Civil War to just after World War II. (2) Georgia is second only to Mississippi in total lynchings (531-581). Terror lynchings were horrific acts of violence where the perpetrators were never held accountable. And many were “public spectacle lynchings.” They were often announced in the local paper and attended by the entire white community, whole families, dressed in their Sunday best as if on a picnic. They were far beyond mere punishment for an alleged crime. They were celebratory acts of racial control and domination.

A new revelation to me, is how often lynching was used to keep African Americans from voting. The “crimes” white supremacists alleged to “justify” these brutal murders were often things like “harassing a white woman” or fabricated witness to rape. Many times the underlying motive was really voter suppression. In fact the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till, a lynching of which even most whites have some knowledge, was about terrorizing potential voters. Till’s crime was “whistling at a white woman” in the local grocery. But after his acquittal, one of the murderers, J.W. “Big Milam” confessed:

I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, [racial slur] are gonna stay in their place. [Racial slur] ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government. (3)

Violent assaults on voter rights began as early as 1866, when, in New Orleans a group of African Americans attempted to convene a constitutional convention to extend voting rights to Black men. As they marched, a white mob began firing on Black conventioners, indiscriminately killing forty-eight Black people and wounding two hundred. Terror lynching in Georgia, at least back to1868 and the “Camilla Massacre.” In Camilla, Georgia, white residents, determined to stop two visiting black politicians from speaking at a rally, fired on black marchers, killing at least seven and wounding 30. Shortly after that, a white mob killed a black man, Perry Jeffreys and most of his family in east Georgia to stop him from voting for Ulysses S. Grant for president. (2)

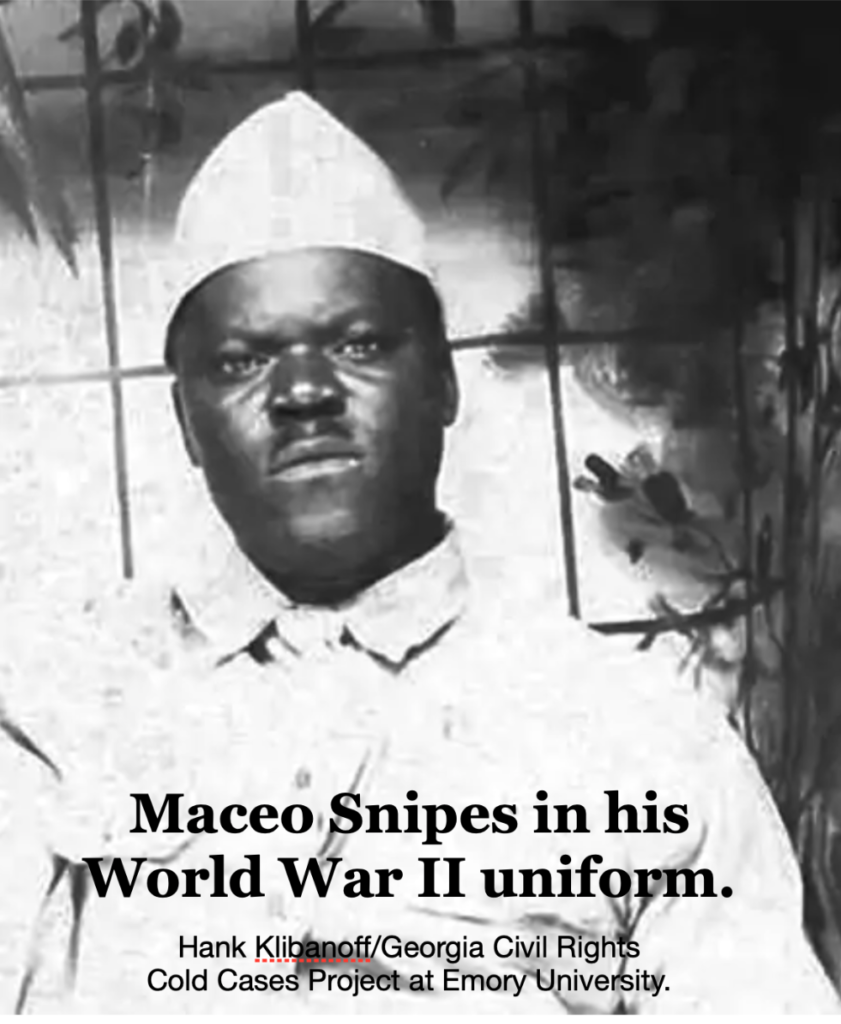

There are recorded incidents of voter terror as late as 1946. In what is known as the “Moore’s Ford Massacre,” two black couples — Roger and Dorothy Malcom, and George and Mae Murray Dorsey, were lynched by the Ku Klux Klan near Monroe, Georgia. Apparently the murder was executed in exchange for political support of a white candidate for governor, but the clear message was “if you register and vote, this will happen to you.” (2) Another 1946 incident was the lynching of Maceo Snipes, a WWII veteran who had served in the Pacific. Having risked his life for his country, he was determined to vote. The clear message from white supremacists across the county was: “The First Negro to vote, that’ll be the last thing he ever does.” When he cast his ballot, July 17, 1946— he was the only Black person to vote in Taylor County. A couple days later, he was shot in the abdomen in his front yard. His mother helped him walk miles to get a ride to the hospital, where he waited for 6 hours. Doctors removed the bullets, but he needed a blood transfusion to live and it just so happened the hospital was out of “Black blood.” In the Jim Crow South, even blood was segregated. He was dead at 37. (1)

The family was told anyone who attended the funeral would also be killed. His wife, stepdaughter and 3 others attended. He was buried in the town cemetery under cover of darkness in an unmarked grave.

His murder and the lynchings of others in Georgia the next week got the attention of a 17 year old student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, who was moved to write a letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution August 6, 1946.

We want and are entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens.

Martin Luther King Jr. (1)

Equal opportunities in education, health, recreation and similar public services; the right

to vote; equality before the law; some of the same courtesy and manners we ourselves bring to all

human relations.

Economist Jhacova Williams of the Economic Policy Institute says it’s impossible to understand black voting if you ignore the history of lynching (check out her youtube video in #4 below). She looked at the data of 3,000 lynchings 1882-1930. She found a direct correlation between locations of lynchings and recent black voter registration. The more lynchings in a given county, the lower percentage of black voter registration. For instance there were 8 lynchings in Lafayette Co. Florida, one per 1,000 black people. Today the black voter registration rate in that county is 15%. She says, without lynchings you would expect 55%:

Lynchings a century ago, reduce black voter registration today. Lynching was the original form of black voter suppression, intended to show black voters what would happen if they tried to participate in democracy, if they tried to vote. So today, when black voters look at the efforts to suppress the vote, whether it’s felon disenfranchisement, voter ID laws, the gerrymandering of congressional districts or the Supreme Court ruling on the Voting Rights Act, it’s impossible to see it without seeing the legacy of Jim Crow, poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and, yes, the terrorization of the black population by lynch mobs. (3)

So friends, there you have it. I quoted a lot of other sources today, because I don’t know these stories and until I started paying attention to them, I could never live as if they were my own. Truth is, they are my stories too. And yours. That’s a big part of what’s at stake today. All up and down the ticket, it seems, we are being asked to choose whether to continue and live segregated destinies or truly join our futures as one.

In Georgia, there is hardly a county where there wasn’t a lynching, so the white mob is very much alive. Thousands of lynching stories have motivated the Black community to push for civil rights and the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 only to have it essentially lynched in 2013, when the Supreme Court struck down key portions preventing states like Georgia from making changes to its voting laws without federal approval. Since then, the state has instituted a strict voter-ID law, closed polling places and purged voters from the rolls. (1)

So, yes, lynching is alive among us still. And the more we embrace it as an ugly but formative part of our communal history and take it to the polls with us, the more we can really understand why we vote and for whom. For lynching is alive in the stories of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery, it is alive in the mob who wants to gut the Affordable Care Act and further string up the Voting Rights Act. It’s alive in the politicization of the COVID mask and the Climate Science. It’s alive in the powers who build walls that separate, who make the undocumented illegal, who lie, cheat and disrespect, who seek to incarcerate when they could empower. It’s alive in those who constantly make law only for themselves, who demonize victims and confuse greatness with the common good. Today, I hope we are voting because we are way better than this. We are all children of God and we must vote so. Whatever happens today, I’m voting for a world where, one day, no one will have to fear the white mob. No parent will have to give “the talk” and everyone can vote in freedom, safety and love. Let it be so.

In this blog, I have re-told stories from these sources and tried to faithfully footnote them:

- Stories of the legacy of voter suppression from the documentary film, “All In: The Fight for Democracy” which chronicles the Georgia gubernatorial race of Stacy Abrams with Brian Kemp in 2018 and shares the legacy of voter suppression in the South. Directed by Liz Garbus and Lisa Cortés, it is available on Amazon Prime.

- The Equal Justice Initiative (eji.org) report titled “Lynching In America: the Legacy of Racial Terror” and their most recent update “Reconstruction in America.”

- Economic Policy Institute blogpost, by Jhacova Williams: “This MLK Day, Remember Emmett Till and Voter Suppression” Jan. 16, 2020.

- Youtube Video: “How lynchings affect black voting today.” by Jhacova Williams, Economic Policy Institute

Pic #5: Please post link to the Jhacova Williams youtube above—should be in dropbox

Thank you so much John. We too wrote letters and pray they made a difference and touched the people who received them. Keep up blogging.

Good job summarizing the issues with voting while black in America.

I too wish to live long enough to see voter suppression eradicated in America.

The number of issues the Supreme Court has gotten “wrong” has been growing in the last decade or so and it could only get worse if the public does not vote in many more Democrats.

Love you summaries, Rouanna