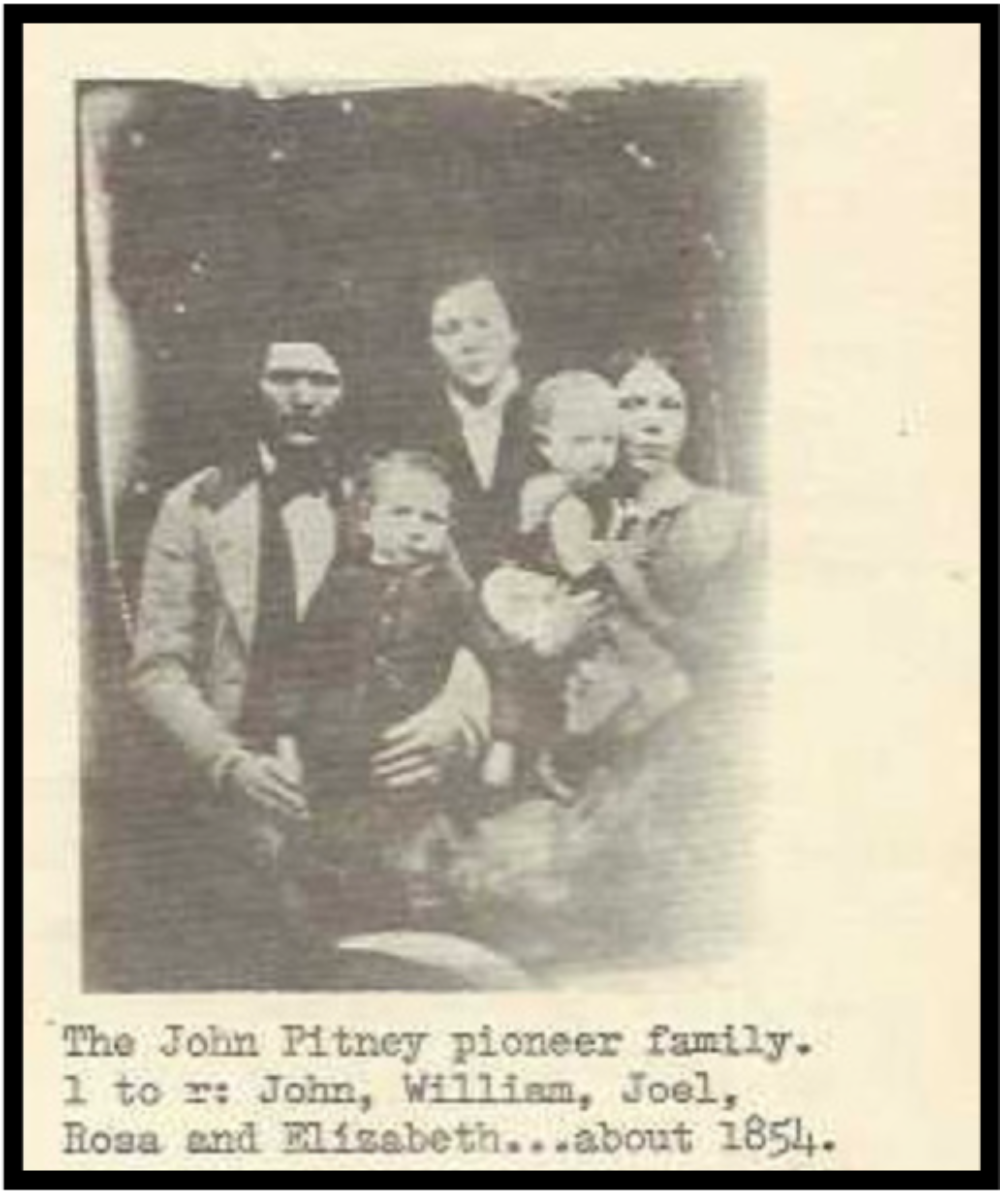

John Pitney, my grandfather and founder of the Pitney Century Farm, was married to Elizabeth S. Wayland in Licking County, Ohio, Mar. 24, 1834. They were given negro slaves as a wedding gift and I was told a few years ago by Warren Hammonds (relatives in Fayette, Mo.) that some of the cabins are still on the place.

My ancestors owned slaves. At 72 years of age, the truth finally caught up with me. I was always pretty sure they did, but all my life I’ve kept myself from reading too deeply into family history, afraid of what I’d find. Born of white privilege I thought I could maintain the narrative of a world that works for everyone by just looking away. Acknowledging the history of chattel slavery as a given in the American experience was a relatively easy intellectual exercise for me as a white male progressive, as long as I didn’t need to personally know any African Americans and the day-to-day violence they face.

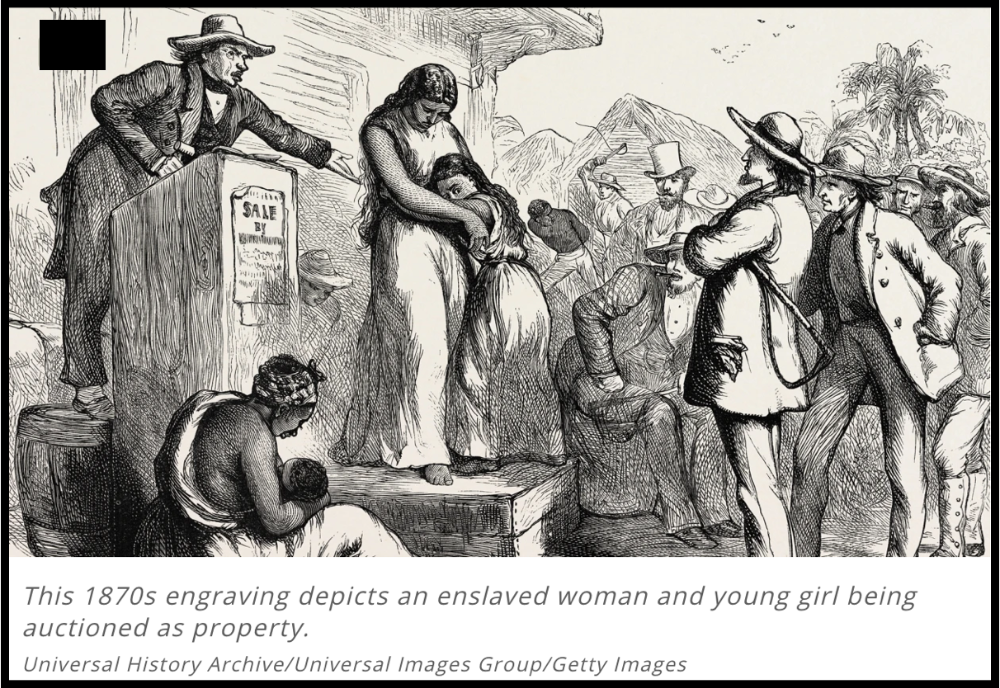

I have always been able to rationalize that mine were the good whites. Those others truly believed it was ordained that some humans could own their human neighbors as property. Those others could, in good conscience, buy, sell and trade black humans at auction like cattle, even give them as wedding gifts. They could deny these humans, born in the image of God, all the rights they themselves take for granted for their own people under the U.S. Constitution. They could even hold good Christian lynching parties in the town square on Sunday after church just for entertainment. But a few days ago I was skimming the oral history my Grandfather Clarence Pitney told from memory and my identity changed.

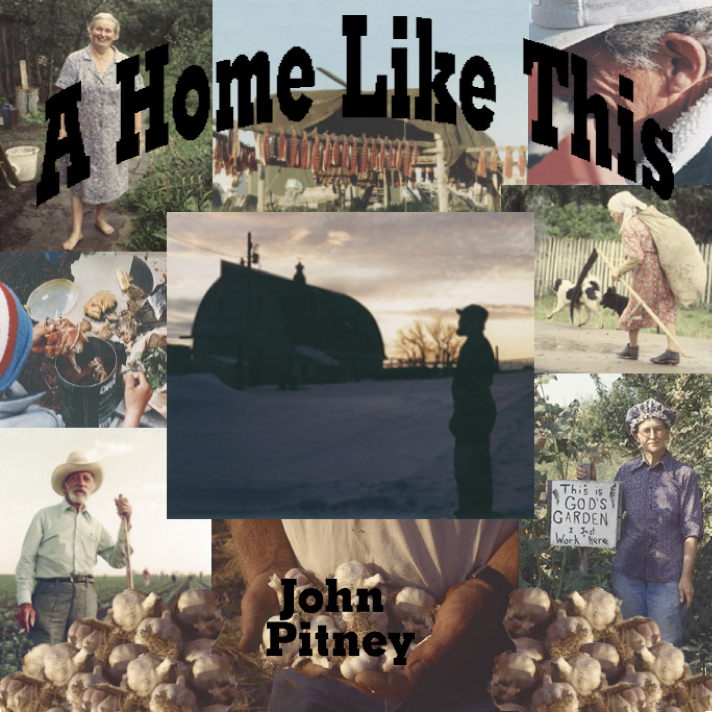

87 Years on a Century Farm, is Grampa’s best recollection of family legend and stories passed down, as transcribed and edited by our sister, Alice in 1976. The book chronicles how our people came from Ireland to America in the early 1600s, settled on New Jersey lands, got to Ohio, then Missouri and West on the Oregon Trail to stake a Donation Land Claim in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. My three sisters and I grew up helping Mom, Dad and Grampa farm the place until we left for college (Mom and Dad would say) “to find a better life.” We were the 5th generation since great great grandparents John and Elizabeth Pitney and James and Elizabeth Bushnell came off the Trail. They staked their claim to the prairie lands, ours designated a “Century Farm” by the State of Oregon in 1959 even though inhabited by other peoples for many centuries more.

Anyway, a few days ago, sister Alice and I were skimming Grampa’s book and we read the words I don’t remember ever reading before. My great great grandparents John and Elizabeth Pitney, “were given Negro slaves as a wedding gift.” Now let me be clear, Grandfather’s book wasn’t published by Random House. Alice did it on a typewriter in 1976 and ran off a few copies on the high school mimeo for all family members to cherish. It is 6 generations of memory of our part of the clan. This episode of a family wedding in 1834, like all the rest, didn’t need to be written down. Everybody knew slaves were given at the wedding. It is curious to me that, after it was written down in the book, it went invisible to some of us on the page. We never saw it. And the story has not been passed on. But now it is no longer invisible, at least to me. Now this part of our family legend can be told and passed down with the rest. Because this part actually changes the whole. Knowing the larger story abruptly curtails my judgement of those other whites as the evil ones. We have seen bondage, and it is us.

The Black Lives Matter movement across our country is a precious gift to our civilization, if we can embrace it. Opening our common history book to the violence of America reshapes our story. Gives it a long-awaited integrity. The sagas of the first slave ship in 1619, the Civil War, Jim Crow and more than 4,000 lynchings change the white supremacist American saga. The brutal legacies passed on in the stories of calculated murders, from the blood of Emmett Till to the slow homicide of George Floyd, seen around the world, plead for us to re-write. My family was so proud of our Oregon Trail inheritance. Each of us got to show and tell in 4th grade when we studied Oregon history. Grampa let us take the hoops from the Conestoga wagons that brought our family from Independence, Missouri in 1853. When we received our “Century Farm” designation in 1959, we got to shake the Governor’s hand! Each time we shared the legend of the Oregon Trail with other whites, we were famous in a way, like they could reach out and touch the pioneer heroes in our flesh! Our blood relations had survived the hardships, the attacks of savages, even childbirth on the Trail to claim our Manifest Destiny in the Promised Land.

When I was in grade school, Grampa organized the first family reunion of our people. Pitneys came from across the U.S. We performed cheesy dramas of our brave pioneers on a make-shift stage in Grampa’s back yard. This was our celebrated identity. When it comes to giving and receiving other humans like property, it would be easy for me to say “well those were my ancestors 6 generations back. We are not them.” That would be far too simplistic. If we are somehow revered today for our people’s acts of bravery, freedom and adventure how should we be known in those actions we never talk about, acts of cowardice, bondage and exploitation? In any conversation with white people about the Trail, someone will say “I can’t even begin to imagine—how did they do it?” And we all nod in unison. To answer the question with any integrity, we will have to ask African Americans and Tribal communities to tell us of their Trails.

And yes. Giving slaves as wedding gifts was a thing. In a column for History On Fox titled “When Giving Human Beings As Wedding Gifts Was Fashionable,” (https://historyonthefox.wordpress.com/, February 9, 2018) Roger Matile writes:

It strains credulity these days to consider there was a time in this country when one person not only owned another, but could simply give them away as gifts. But the custom was common for the first two centuries of the European settlement of North America. But nevertheless it’s true.

Shonda Buchanan, in her podcast PushBlack Now: Daily inspiring Black stories Just for You (Mar. 20, 2021) adds more:

These “gifted” children, as young as 3 or 4 years old, were separated from their families and forced to clean, run small errands, and help cook. They later became field workers, forced concubines or were sold. Historian Michael Tadman says one third of enslaved children in Maryland and Virginia were separated from family “by sale away from parents.” Children could also be bequeathed in a will after a slave master’s death. Frederick Douglass wrote that “slaveowners purposefully separated children from their parents in order to blunt the development of affection,” effectively destroying their childhood.

In fact, our great great grandparents, in celebration of their marriage in Licking County Ohio in 1834, were participants in a cruel and cultish conundrum. How can one celebrate a new step in the development of one’s own affections while, in the same ritual, crushing the affections of others? I’m sure the white clergyman in charge, officiated God’s eternal blessing on all of it. Praise Jesus.

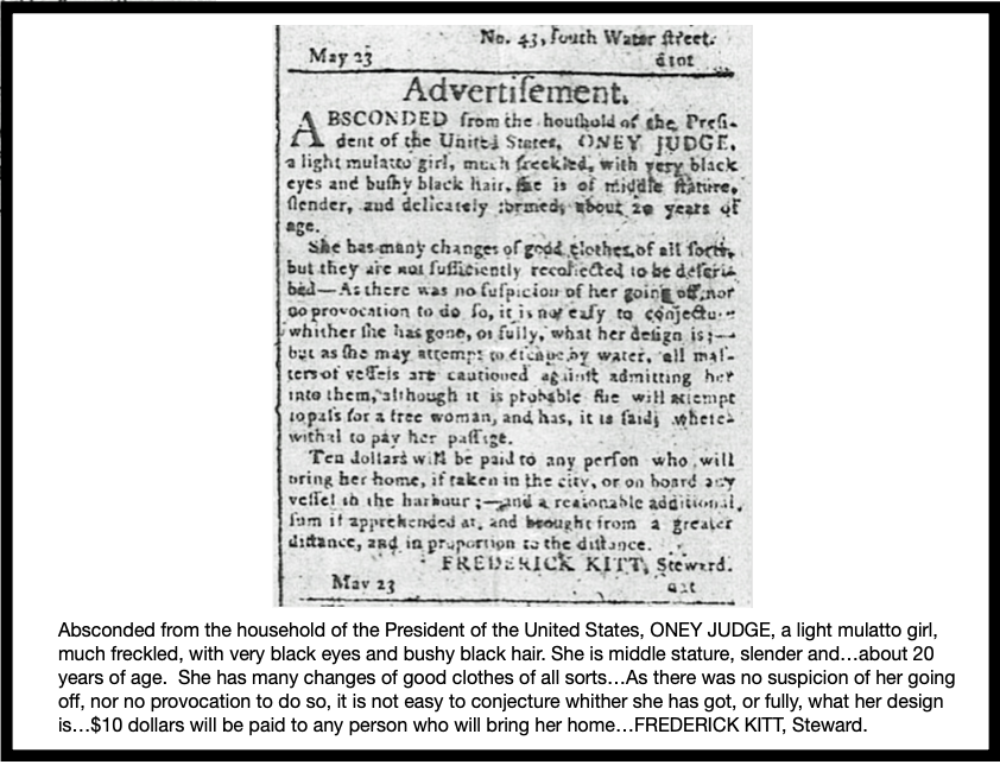

Columnist Roger Matile, as quoted above, tells the story of two women given away as wedding presents. Ona Judge was a slave to the household of George Washington, President of the United States. She’d moved with the family and The President’s stable of slaves from Virginia to the Capitol in Philadelphia when Washington was elected. The Philadelphia headquarters was temporary while the D.C. building was being constructed by slaves! In the spring of 1796, when Martha Washington informed Ona Judge she would be a wedding gift to Martha’s granddaughter, she planned her escape. In May 1796, she slipped out to the home of a free black family while the Washington’s ate dinner. As she escaped to New Hampshire, married a free black seaman, raised a family and learned to read and write (prohibited in Virginia) she lived looking over her shoulder as the angry Washingtons pursued her around the territory the rest of her life. See this copy of a warrant and reward for her capture and return.

The other story Roger Matile tells is of Ann Lewis, who, he says:

. . . was literally ripped from her family at the age of seven years when her owner, John Gay, a wealthy planter in Woodford County, Kentucky, decided to present the child as a wedding gift to his daughter, Elizabeth, upon her 1842 marriage to Elijah Hopkins. The Hopkins settled with Elijah’s family just across the Ohio River in Ohio. And while Ann started out as a slave, in accord with Ohio law, she was freed the minute she set foot on Ohio real estate.

Matile goes on to describe how, although free, Ann Lewis continued to live with the family who had enslaved and freed her, helping the couple raise several children. She moved with the family to Illinois in 1857, then married farm hand Henry Hilliard. She and Henry farmed and raised a family together in two different Illinois communities.

Two women, both slaves, two journeys. Ann Lewis died at the age of 106, free as a black woman could be in a country that didn’t recognize freed slaves as full human beings. Ona Judge was classified an escaped slave the rest of her life and so too her three children. Even born in a free state and their father a free black man, Virginia law insisted since they were the children of an enslaved mother, Ona’s three children, too, were enslaved and were the rightful property of Martha Washington’s heirs. Roger Matile concludes his column this way:

Two enslaved females were given as wedding gifts, something that led to freedom for one and a life of worry about losing the freedom she seized for herself and her children for the other. “In nothing was slavery so savage and relentless as in its attempted destruction of the family instincts of the Negro race in America,” wrote educator, political and women’s rights activist Fannie Barrier Williams. But Ann Lewis and Ona Judge figured out how to defy that very effort.

—Roger Matile, “When Giving Human Beings As Wedding Gifts Was Fashionable,” Feb. 2018

These two women “figured out how to defy that very effort.” That’s the legacy, right? It’s the strength, perseverance and heroism of Ona Judge and Ann Lewis. My first impulse was to make this about which slave owners treated their slaves best. And how modern whites can also choose to live more justly. But I don’t want to go there. Getting serious about searching our family trees for evidence of human bondage, we found those stories of somebody’s great great grandmother who was “kind” to her slaves…how she read to them from the Bible every Sunday afternoon. I’m sure she loved to quote them chapter and verse: “Slaves be obedient to your masters.” (Ephesians 6:5). Further, the brutal treatment of Ona Judge at the hands of George and Martha Washington certainly stands in stark contrast to what Ann Lewis received from her benevolent captors. In the same way, our family history tells of John and Elizabeth settling in Missouri for awhile but moving on to Oregon because Missouri was slave country. Our white grandparents told tales of how they stood up to the Klan in the West, how they formed new church congregations of Union sympathizers when their former ones split over the Civil War. Seemingly they were always on the “right side.” There will always be, in the annals of Truth, sagas of white goodness. The tragedy for white people is that the dominant story has always been told by us about us. We are the heroes and heroines. We persevere against all odds. We survive at all costs. We are the ones God protects and blesses. It just can’t be about us anymore. Because it’s not about us. We inhabit lonely branches on the human family tree. I want to tell a more truthful legend.

For our own history, we don’t know how slaves were being given as gifts in an Ohio wedding in 1834. Slavery was abolished in Ohio in 1802 and, if it mattered, Ohio also had the most stations (300+) on the Underground Railroad of any state. We don’t know what happened to Pitney and Bushnell family values concerning slavery, life, liberty and property, between 1834 and arrival in Oregon in 1853. Great great Grandfather James Bushnell, in his autobiography, quoted his brother Corydon, who said his wife’s father was a slave owner who willed a slave to each of his children. So, he said, at the time of their marriage in 1857, his wife owned a “colored girl” that her father bought in Missouri for “$1,000 plus her hire for a year.” He related that “the wives of slave owners always had one or more colored women to do their housework and the daughters each had a colored girl to wait on them so they seldom learned to cook or do housework.” Consequently, traveling the Oregon Trail and upon arrival in Oregon without any slaves, she didn’t know how to cook, clean or do any useful work around the house, let alone on the farm. But, apparently, when freed of her slaves, she learned how to work.

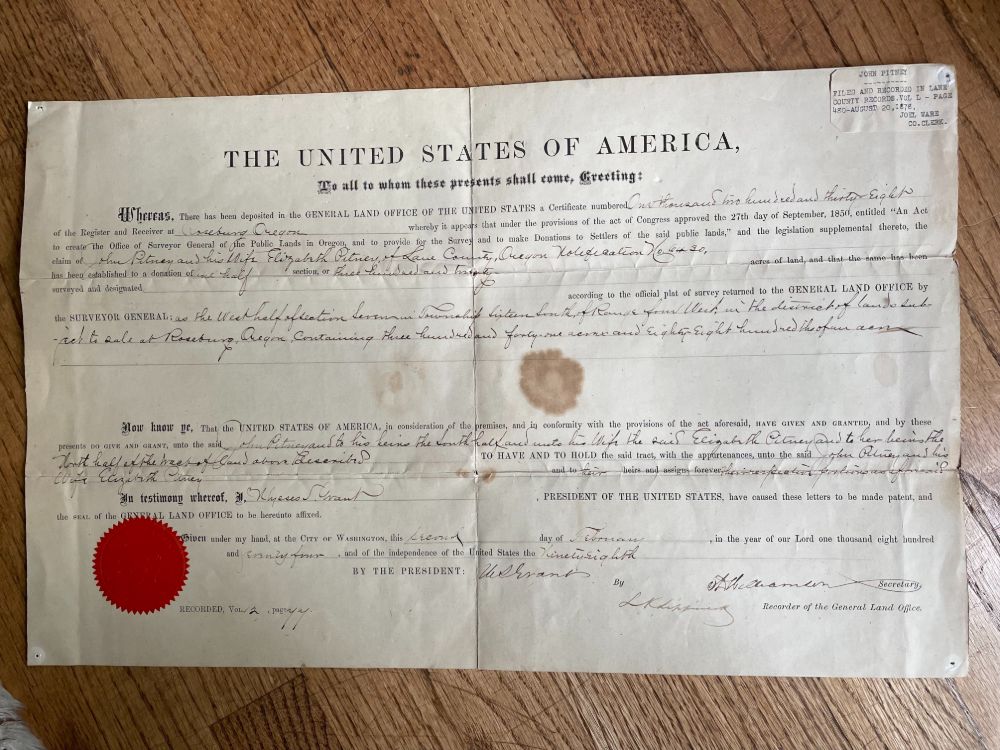

The last few years of his life my Grandfather Clarence lived with Mom and Dad in the room that was my bedroom in our farm house growing up. On my bedroom wall, Gramps hung the Pitney Clan’s most revered document in full view. I would marvel at it on visits home. It patented our right to own the land on which we lived, pursuant to the Oregon Land Claim Law. The law, when our families arrived in 1853, deeded free land, 160 acres each for a husband and wife who would live there and build on it. It displays the red seal of the General Land Office of the United States of America and bears the real ink pen signature of President Ulysses S. Grant. More than anything else this document proved our right to be here. It claimed and projected our identity. It contained the fundaments of the white American narrative to which I was pretty much oblivious. What I did not realize until well into adulthood was that the Oregon Land Claim Law prohibited slavery, but didn’t allow African Americans to live in Oregon. You could own land if you were a white male, if you were married to a white male or if you were a “half-breed” Native American male with at least 50% white male blood. As carried out, Blacks, Hawaiians and single women also weren’t welcome in Oregon. (“Oregon Donation Land Law” by John Scott).

The narrative is an Eden where only white males are fully human, white Christian males are entitled to any land or resource on which they plant their cross before another white Christian male can plant his cross. The narrative is a Promised Land where only white Christian males are allowed to make the rules that determine which narrative wins.

My wife Debbie and I were married within 30 miles of the site in Licking County, Ohio where John and Elizabeth Pitney received a wedding gift of slaves and exactly 140 years hence. We did not receive slaves as gifts. Instead we were gifted a whole world of white privilege and privileges. After 47 years of marriage in 2021, I am not sure the American story has fundamentally changed that much. I remember Dad and his brother, Uncle Elvan, saying they had a dog named Blackie on the farm when they were kids. Everyone knew the dog’s original name was “N___er.” Names are important, but changing them is only a minute step, like lipstick on a pig. To know what’s changed we must listen to the children of former slaves and our neighbors on the Reservations of our land. Because the questions still remain: Who is fully human? Who are entitled to land, resources & wealth? Who are allowed a voice and vote to determine our narrative? What I think I know is that we are creating small Edens where we answer more truthfully. My sisters and I have just sold our farm, but we need not sell out our truth. We still have a chance to tell our story differently and pass on a narrative to our children, grandchildren and neighbor children more true. I don’t feel guilty that our people owned slaves. A faux sense of guilt is such a convenient white American excuse not to act. I do feel a deep, deep sense of responsibility to be a story re-teller. We can all do this, right?

And our neighbors of color are saying “To hell with your guilt!” anyway. To get serious we must make reparations and that’s what I want to be part of with the time I have left. For today, however, it’s important for me to let this sink in, to not act without serious reflection. The words say, “They were given Negro slaves as a wedding gift.” I need to start by asking, after decades of reading and re-reading Grampa’s book, why was I blind to these words?

John, thank you for these words. On this day of the acquittal of a murderer in WI, I am grieving and your words add grief and yet your honest reckoning and call to reflection offer me hope for me and our world.

Awesome job John! It really does make you think. I just finished reading a book called Worthy Brown’s Daughter by Portland author Phillip Margolin. It was a slave story set in Portland, in the same time frame as your article.

As soon as we say to ourselves, “…we are not them…” we’d benefit from taking a good, long look around. And perhaps notice how we, in fact, are them–though it manifests differently. As one example among many, our privilege gives us abundant oil to burn, oil extracted from the lands of people whose health, safety, and lives in real time, in this era, on this day are severely affected by that extraction. Clearly, our own lives and those of our children and grandchildren are and will be increasingly severely affected. Though not as personally as our ancestors, but perhaps more broadly, we go on enslaving other humans. Thank you for sharing your good, long look around.

Thank you, John! I know that my paternal “grandfather” was a member of the KKK in Oklahoma and Texas. I don’t know that he was involved once he moved to Corvallis but his racism stayed close to him. My mother did everything she could to shield me and my brothers from his influence. He served as chief of campus police at Oregon State College and, as he confessed to my mother toward the end of his life, he did everything he could to make life on campus difficult for students of color – particular those “Nigras.” This confession was not an act of repentance, just an acknowledgement. I put the “” around grandfather above because it turns out he was not likely my biological grandfather. His sisters claim that my father was the product of a sexual liaison between my grandmother, his wife, and the family doctor. While that brings me some sense of relief it opens up a whole other line of potential inheritance to explore. The trials that have filled the news this week point so clearly to the facts of the systemic racism we still live with in this nation. And, just maybe, forces us to open our eyes to the suffering we have wrought.

I love this, love the discovery both external and internal. In it I hear echoes of one of my favorite Wendell Berry books, The Hidden Wound, which is appropriate because I only started reading Berry thanks to John. I’d been locked in some ridiculous resistance, and when John heard it, he ran and got his collected/selected and read outloud to me, over the phone long distance on a gray winter morning, “The Birth.” I’ve been a Berry disciple ever since, and a devoted advocate for John’s work. Keep up the good work, Brother.

Thank you for telling this story, John. I suspect most of us white people could tell similar stories if we knew our family history. I don’t know the details of mine, but my mother’s ancestors were white southerners, and one of them was a major in the Confederate army, so I can make a good guess about them. I know I want to make reparations, as I am able.